The History of Megaphone Exhaust, More Than Just A Pipe !

First introduced over eight decades ago, the megaphone exhaust revolutionised engine gas-flow...

There was a time when an exhaust’s purpose was so very simple – to keep debris from entering the exhaust port and to redirect noxious, burnt gases to the rear of the motorcycle. Not much thought was given to performance, especially at the turn of the 20th century when people knew very little about the importance of gas flow, or valve overlap, for that matter.

Most motorcycle manufacturers equipped their machines with constant circumference cylindrical steel piping, concerned most that their shapes weren’t unduly prone to compromising ground clearance or burning the legs of the rider.

Getting Rid Of Gases

The 1920s were perhaps the most innovative years of engine development, with an abundance of manufacturers and fantastic engineers constantly developing new and exciting methods to increase performance figures. Surprisingly, especially when you consider all the experimentation that was going on, very few people turned their sincere attention to tuning exhausts, quite simply because they didn’t know how to tune them or what they should be tuning them for.

Engineers began to appreciate the restrictive effects poor exhaust gas flow was having on motors, actively hindering their ability to omit spent gases and restricting the following pulse of exhaust gases from making it down the pipework. To combat this, many manufacturers tried many different things to enhance the flow, including AJS, which came upwith the 350cc Big Port, which had, as the name suggests, a big exhaust port and an accompanying larger-than-normal exhaust pipe diameter.

Although the idea was theoretically sound and the motorcycle achieved significant sporting acclaim when Howard Davies won the 1921 500cc Senior TT on his Junior TT capacity bike, the reality was that slotting a larger bore pipe on an exhaust was not the answer to the problem of gas flow. By doing this, it is likely to reduce the velocity of the gas being sent down the pipe to such an extent that the flow will essentially lose energy and stagnate, creating turbulent eddies in the pipework that, in turn, compromise the next charge of gas pulse being fired down the system.

Rudge was one of a number of other companies that also tried to improve gas flow, opting for a four-port cylinder head (two-inlet, two-exhaust), as was readily being used in the aeronautical industry. The thinking was that by having two exhausts, one from each exhaust port, twice the volume of gases would be emitted at any one time. The reality was that the split system compromised the velocity of flow down both exhaust systems, to such an extent that some people would block one of the two ports to focus the gas flow down a single exhaust.

Many other fantastical ideas were tried but, as was later to be discovered, the secret to efficient waste gas dispersionwas far more complex and necessitated the understanding of many different factors, such as turbulent and laminar flow, pressure pulses moving at the speed of sound and the effect of internal steps, ridges and bifurcations.

Shaping the Future

When exhaust gases exit a system’s pipework, they are not at a constant pressure. They contain the pulse signature of the cylinder(s) combustion gas as released by the exhaust valve(s). As these pulses escape from the pipe, the opposite sign is then ‘reflected’ back upstream to the exhaust valves; A positive pressure pulse returns as a negative pressure pulse and a negative pressure pulse returns as a positive.

Most motorcycles came equipped with relatively similar sized exhaust pipe bores well into the 1930s, retaining the same internal diameter from the inlet of the system to the outlet. Generally speaking, a smaller pipe bore will encourage a faster gas velocity, moving at higher pressure than a larger one. But only to a point – an overly large diameter exhaust pipe will introduce turbulence into the exhaust gas, robbing the whole system of the ability to utilise pressure pulses and reducing overall flow. So the challenge was to reduce the internal flow pressure of a system, while maintaining sufficient velocity to ensure the gas pulse had the energy it needed once it reached the pipe’s outlet.

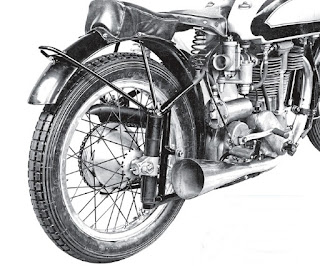

By the 1930s, pioneering designs were everywhere, most of which had been influenced by aircraft development projects, an arena which enjoyed far greater, government-backed financial investment than the humble motorcycle industry. This being the case, aero and motorcycle exhaust orientations had very different objectives and consequent directions. But it’s very likely that Norton’s ‘works’ racing manager, Joe Craig, took inspiration from aircraft exhaust designs when he began experimenting with conical-shaped exhaust systems on his team’s race bikes.

In 1934, Norton competed in the Belgium TT with a bizarre-looking race pipe, shaped similarly to a megaphone. The performance results were positive, so over the following few years the British manufacturer, along with several other firms including the German brand DKW, were to experiment with megaphone designs, culminating with Norton winning the 1938 Senior TT with its megaphone-equipped 500cc Manx racer.

While the exhaust headers remained constant in circumference, the tail end of the pipework – the megaphone section – featured a 1:8 expansion ratio that designers found aided exhaust gas flow and improved peak horsepower by a claimed 7-8%. The unique flared-shape of the system encouraged the gas stream to gradually expand as it exited the exhaust, rather than ‘bursting’ from a plain hole.

The upshot being that the magnitude of the reflected pressure pulses induced by the pipe exit were reduced and spread over a broader frequency. So rather than having an exhaust pipe that worked perfectly at one single rpm, but poorly at all others, the system worked reasonably across a broader rev-range.

Megaphonitis

For all its many advantages, the megaphone design was far from perfect. As the new innovation became the norm in racing circles, with most major manufacturers adopting the flared ending to their exhaust systems, more and more people would come to complain of poor low down performance – ‘until it came on the mega’.

Dubbed ‘megaphonitis’, the problem with the broad mouthed mega was its susceptibility to creating the wrong kind of pressure waves at low revs, which would bounce back down the pipework and impede the flow of exiting gases. By persisting with the throttle held open, in most cases the gas flow would eventually improve at higher revs and the symptoms would vanish. For this reason megaphones lost favour on tight and technical circuits, where it was impossible not to depend on the lower scale of an engine’s rev-range, meaning you had to ride through an area of rough engine performance before the gas flow righted itself in the top-end.

Many different ways were considered to cure the problem, including making changes to the jetting and air slide gap, but there was no magic cure. Of course, on circuits such as the TT, where the core of the racing witnesses fantastic speeds and a much higher dependency on top-end revs, the megaphone was still favourable. But in other environments, the traditional constant radius systems proved more favourable.

The Peashooter

In a bid to improve the situation, megaphones were then produced with a ‘reversed-mega’ cap at the very end, such as the 1957 AJS 7R, which saw a 1:9 ratio of megaphone, with a reverse cone exit that was around 40% smaller than the diffuser. The change of shape altered the backpressure drastically and is claimed to have significantly helped in eradicating megaphonitis.

As a direct consequence, the peashooter design became massively popular and went on to influence many manufacturers’ exhaust designs over the next few decades. Evolving as it went, another change made to the peashooter system was to extend the length of flare quite significantly, while simultaneously reducing the exhaust’s outlet diameter.

Today's Designs

Huge advances in gas-flow diagnostics, plus the introduction of much stricter noise and emissions legislation, has seen a whole new orientation in exhaust profile and thinking.

This being the case, the ‘mega’ exhaust still holds a firm place in the racing paddock, being the chosen sting-in-the-tail design on most Moto GP factory exhaust systems. Naturally, the design of today’s megaphones is significantly different to the likes of what came about in the 1930s, but the principals remain the same. History has a funny habit of repeating itself.

Honda VTR1000 FireStorm, Sweet & Comfort !!

My earliest memory of a Honda VTR1000 FireStorm came in early 1998, when a copper pulled me up on one for going a bit sharpish.

I’d love to tell you the story of how said officer of the law passionately threatened to seriously adjust my licence, but then suddenly (and thankfully) had a change of heart, but that one's best recalled down the pub. What is worth noting was his enquiry about how good I thought the Honda was before letting me go on my merry way. “It’s not a Ducati,” I replied. My assessment was a bit more detailed and elaborate than that, though in essence that was the crux of the matter.

Honda VTR1000 FireStorm : Detail

Nigh-on two decades later, after another blat on a VTR, that’s still pretty much how I feel. Now, not being a Ducati works both for and against the Honda. Not being built in Bologna means having a lot less character and personality and somewhat reduces its endearment as a consequence. You’re just never likely to love a Honda VTR1000 FireStorm as much as a Duke. In saying that, you’re probably not going to feel some of the other more negative emotions sometimes associated with running a 90s Ducati either.

Keep a Honda VTR1000 FireStorm in your garage and though you might not be as thrilled every time you open the door, there's a good chance its reliability and dependence will make ownership feel just as rewarding – just in a different way. Living with a VTR can be a whole lot easier. Only one key thing is wrong with the Honda in my book, but we’ll come to that later. It might have been a very long time since my last spin on the Japanese V-twin, but this one didn’t take too much time to win me over. Slim and light, with a fairly simple and elegant style, the Honda has a purposeful feel to it. Its build quality and finish is of a robust nature too. This 2000 model is in very good order for its vintage, which is no surprise perhaps, as it’s been pretty well cared for and comes from an era when Hondas were noted for their durability.

Get it fired up and the sound it makes is just as appealing. Again the traditional deep note from the Honda VTR1000 FireStorm twin pipes can’t quite match the magical music of a Duke, but the cans still play a very pleasant tune. With eyes and ears satisfied by nice sights and sounds, the engine then gives plenty of stimuli to the heart. I’m well aware that not everyone likes the way V-twins make their power, but I’m a big fan. Just like the VTR, they generate speed so easily. A claimed 100 and odd bhp isn’t much to shout about these days, but because what power the Honda does have can be accessed so easily, that relatively low figure is pretty academic anyway.

Honda VTR1000 FireStorm : Performance

Twist the grip and there’s always something to drive you forward meaningfully. You certainly don’t have to wait like you sometimes do on most fours. There’s no requirement for the crank to get up to speed before the cumulative effort of its attached pistons is delivered. Instead, just feed the big bores with unleaded/fresh air mix and the VTR1000 FireStorm big pair of alloy slugs instantly pump the bike forward.

The Honda VTR1000 FireStorm punch feels strong and prompt at all revs, making speed gains simple enough to make it feel like you’re cheating. The obedience does have a bit of a trade-off with very low rpm in the big gears and chugging through town needs a bit of technique to maintain smooth, snatch-free progress. Having sampled these motors for years now, it’s not a chore for me to juggle gears and rpm, and sometimes use a bit of clutch to refine matters further, but I do always bear that need in mind whenever running through the urban zone. However, out in the sticks the keen throttle response and the motor’s relaxed feel offer plenty of compensation.

Also allowing the speed to feel nicely controlled is the Honda VTR1000 FireStorm chassis. Not necessarily what you’d call super sharp, you can still hurry the fairly agile, sweet-steering Honda along at a swift pace when the roads deviate in differing directions. To be honest, I reckon I’d probably spend a few quid and get the suspension upgraded a bit if I wanted to get the absolute best from the bike down backroads.

In standard trim, Honda VTR1000 FireStorm damping of both the forks and rear shock can feel a bit dead and wooden when you’re trying really hard, especially over some rougher routes. Chucking some money at the brakes wouldn’t be a bad plan either. They’re certainly not what you’d call lacking, though I’m sure with better pads and some braided hoses they'd have a fair bit more bite and feedback.

What’s more than OK without any need to open your wallet is the Honda’s comfort. Stick a bit of luggage on it and the VTR can happily cope with longer runs thanks to its typical Honda riding position with its famed one-size-fits-all, roomy and relaxed feel to it. That plus point is handicapped by the VTR1000 FireStorm one main weakness though – its poor tank range. It’s a sad oversight and the only issue that spoils a generally very positive appraisal of the Honda. If you’re lucky and just taking things easy, then you might get around 110 miles before the fuel light comes on.

More likely, especially if you’re giving it some, is the ‘get some fuel pronto mate’ bulb will come on at around just 80-90 miles. That really does limit the extent of the bike’s pleasure. This bike was slightly better as it had a larger 19-litre tank bolted on from a later model, the owner having become too cheesed off with visiting the pumps too often.

Verdict :

Not everyone will find this issue spoils what is fundamentally a solid bike though. On the whole, the Honda VTR1000 FireStorm performs well and even has a bit of rarity value to it these days. And though it might not be able to match a Ducati for sheer sex appeal, real world virtues mean it’s still got a lot going for it – as long as you’re prepared to keep filling the bugger up anyway!

Motorcycle Event : Shelsley Walsh Bike Festival

If you like getting up-close and personal to a wide array of historic motorcycles, then the Shelsley Walsh Bike Festival is for you. The festival will feature large displays of historic and modern machines, as well as race bikes, plus a Paddock Specials area, motorcycle clubs, passenger ride experiences, an autojumble, live music, biker celebrities, and trade stands so there’s something for every biker.

Shelsley Walsh Bike Festival gives you the unique opportunity to get up close and see lots of historic, classic and modern race bikes and watch, smell, hear and see them run the historic hill climb course. Entries for Paddock Specials are both by invitation and by application – so if you own a historic bike, the organisers want to hear from you via their website. Shelsley Walsh is the oldest motor sport venue in continuous use in the world, being first used in 1905, making it older than Indianapolis, Le Mans or Monza.

One of the highlights will be legendary motorcycle builder Allen Millyard taking to the hill on his home-built "Flying Millyard" – do not by fooled by its appearance, despite resembling a vintage motorcycle, this beast is powered by a gigantic 5.0-litre V-twin engine designed for an aeroplane! Shelsley Walsh Bike Festival promises to be a great day out for all motorcycling enthusiasts.

What’s more on Shelsley Walsh Bike Festival, all event proceeds go to The Nationwide Association of Blood Bikes and Severn Freewheelers.

The event is held at Shelsley Walsh, Worcestershire WR6 6RP at September 13... and entry is £15 on the day or a tenner in advance with kids under 16 going free. It’s free parking, bikers get a free sidestand puck and free helmet park for bikers Gates open at 8.30am. For more go to: www.shelsleybikefestival.co.uk

Road Test : 2015 Kawasaki Versys 650 vs Old Versys !

In 2006 Kawasaki released what was, on paper at least, a competent, good value, easy to ride machine. While off-road pretensions were considered, the ‘Versatile System’ was created for the wants and needs of the whole EU market – a slightly older audience that would be riding mostly on the road. More Range Rover Sport than Land Rover Discovery.

If that leaves you feeling uninspired, you couldn’t be more wrong. For good reason, a loyal following has built up around what some have previously described as ugly; it’s a relatively inexpensive bike that is far more than the sum of its parts.

The Kawasaki Versys name is wholly appropriate – this is a bike as happy nipping to the shops as it is crossing continents. It’s a road-bike at heart, and despite its relatively low price and basic suspension, it handles incredibly well.

A Proven Power-Plant

The Versys’ 649cc parallel-twin has proved itself a reliable, solid motor in this, the ER-6 and now the Vulcan S.

The engine was always intended to be a modular unit for middleweight platforms, but there was much debate over whether it should be a V-twin, a triple, a four or a parallel twin. For many reasons, but mainly due to size, weight, cost and the potential speed of manufacture, the idea of a twin won through. We’re told the engine was close to becoming an in-line four, but the power delivery of two cylinders was preferred... but then configuration was a question.

The ER-5’s motor was a straight forward parallel twin benchmark – in spirit at least the engine donated by the GPZ500S was half of a GPZ1000RX, so the discussion began of which engine of the time would be the inspirational big-brother. The ZX-12R started the thinking behind the ER engine, and the long deliberation of cylinder angle and aesthetics.

Avoiding a web of ugly external coolant pipes meant designing internal water passages. The gearbox became a racebike-style cassette design, though for manufacturing reasons, not racing image; the Japanese company was already planning to set up facilities in Thailand, so simple assembly methods were ideal.

The idea was always to create just one base engine that would be adaptable to other uses – fast revving and sporty in the ER-6f, mid-range commuting performance in the ER-6n, with slight changes for the Versys and for cruising in the Vulcan S.

More Than Just A Prettier Face

The MkII Versys saw a facelift that still had its detractors in 2010; popularity rose, but the 2015 redesign was created after realising that the potential market of the bike could be younger. Wanting to maintain the original audience, but at the same time excite a new market, the ‘family’ styling now reflects the DNA of the ER-6f and Z1000SX.

The Sicilian press launch of the new 650 showed that this was far more than a new set of plastics; Kawasaki appeared to have addressed customers’ complaints of weak brakes, poor screen, soft suspension and engine vibration, but the best way to see if the engineers had really got it right was to lend it to the owner of the previous model.

Our tester, Graham Mudd is an Army installation technician. An IAM rider and Blood Biker, he mainly uses the bike for fun now, but has done plenty of miles commuting since he bought the bike new in September 2013; “When I used to get called away a lot, I’d throw everything in the panniers to go down and meet the team. It was all on the M6 and M25 – I couldn’t be bothered to sit in traffic, and I had to pay my own fuel, as work provided a van, but it was worth it; I could go for a blast while I was down there, calling in at the Poole Bike Night and other meets.”

Graham, now 35, has had bikes since he was four, when his Dad built him a custom fuel-in-frame C50; “I had a TDM850 before this, but I was spending too much keeping it working. My wife just said; ‘Look, cut your losses. I’m happy for you to buy a new motorcycle, but you’ve got to keep it for a long time, and you’re not allowed to modify the engine.’

" Bolting bits on is fine, but every problem I’ve had with bikes has happened when I started tinkering with the engine; my Bonneville broke when I was running hot cams and a 35mm flat-slide carburettor. I did have that 10 years, and got 102,000 miles out of it though. I like adventure bikes; maybe not as big as the GS, but I wanted something that could do it all; that could tour and commute."

"I loved the TDM, so wanted something in a similar vein, but more modern. It was practical, tall, and really comfortable, but the TDM was just getting old. So the long process of test-riding the V-Strom, Transalp, WK650, Versys and more began… I did a shortlist of what I wanted in a bike – the pros and cons. I eventually narrowed it down by price to the Versys and V-Strom, but the Suzuki was just a little bit tall for me [Grahamis 5ft 9in] – I was on tiptoes at a standstill. "

"A lot of people say it’s ugly, but I like it. It’s very functional, and I like that. It looks like it could take a hit and stay the same... like a boxer! I’m usually quite practical in my decisions; the only bike I’ve ever bought on impulse was a Kawasaki ZXR750... never again. It was beautiful, but it put me off sportsbikes for life. I bought it on a whim when my GS500 caught fire, and got it because it looked so good. I should have ridden it first... After a year I chopped it in for the Bonny."

The Versys is what many would call a "great beginner’s bike", but to let it languish under that moniker is to do it a huge disservice. Graham is an experienced biker, and while he’s owned bigger bikes, the 64bhp of his Versys is plenty: “My dad always reckoned that an 800-900cc triple was the ideal engine configuration, but I like the parallel twin, and this is powerful enough to be fun. It’s not enough to get a novice into trouble, but it’s not so under-powered as to be boring; very few times have I ever wished for more.

Back to Back Riding

Somehow, while riding west of Stafford, Graham and I encountered warm sun, cool cloud, rain and snow. Rolling hills, busy towns and mudstrewn roads all put both bikes to the test, and proved the 2015 bike is built on an already solid platform.

You’d be hard pressed to claim the newer model was much quicker, or that it handled like a completely different machine, but the refinements certainly make a difference; “Kawasaki clearly listened to its customers, and made improvements where they were needed,” said Graham after riding the 2015 bike. “The OE tyres are better than you got with the Mk II and the front-end doesn’t dive like mine. Top gear roll-on seems to have more go – I’d probably have changed down on the older one. The induction roar from the new airbox is great too.

“It really is a much better bike. It’s nothing major, but just the little bits here and there make it a better bike as a whole. The screen’s not as protective as my aftermarket Givi, and I missed the handguards and heated grips. The brakes are a vast improvement though; mine has braided lines and it’s still not brilliant. The new seat is better than the original, but I’ve got the aftermarket gel seat; it’s better than the standard one on the new bike which is a bit too soft."

“I’m glad they haven’t changed the engine or the chassis too much – that’s what made the Versys such a great bike. It still handles brilliantly – it’s still got that agility and crisp handling that I always liked. Kawasaki has done a good job.”

Verdict :

So what did I think? The Versys is clearly a big improvement over an already accomplished bike. Graham’s machine suits himdown to the ground, and I’ll ruthlessly plagiarise many of his mods with my long-term test 2015 Versys 650. My 125 mile ride home as the sun started to drop was one of the best I’ve had in years; the Versys is everything its spec sheet indicates, but the combination of practicality, efficiency and low-price create a bike that’s much more, well, versatile.

Yamaha NMAX 125 Review : Tech On A Budget Scooter !

Yamaha NMAX 125 has variable valve timing and ABS as standard – fancy tech for a scooter, so what’s the story ?

Yamaha’s mission with the NMAX 125 was to challenge the best-selling Honda PCX on its home ground, with a fuel efficient scooter featuring more sports appeal and some big-ticket gizmos – hence the ABS and Variable Valve Actuation (VVA).

At the heart of Yamaha NMAX 125 is a brand new engine, one that Yamaha admits will be used by other scooters in the future. Frictional losses are cut by a claimed 18%, with attention paid to piston rings, the cylinder bore lining, crankshaft oil seals and a roller-bearing rocker arm. The result, says Yamaha, is an ultra efficient motor that does 107 mpg on the WMTC cycle (Honda claims 133.9mpg for the PCX on the same cycle). With a claimed top speed of 62mph, this is definitely an urban scooter, but it’s as easy to ride as any other twist ‘n’ go (more than some), thanks to the low 765mm seat, which is still roomy enough for most of us.

Yamaha’s VVA is relatively simple, with two different cam lobes – one tailored for low-speed torque, the other for high speed power. A solenoid flicks between the two when the motor passes 6000rpm. In practice, you wouldn’t know it’s there, as there’s no power step when the high-speed cam kicks in. Acceleration is nicely brisk from the lights and just keeps going, as linear as you like up to 50-55mph.

The Yamaha NMAX 125 is certainly fast enough to keep ahead of city traffic and it doesn’t get much more manic than Lisbon at rush hour. We didn’t get the chance to properly check the top speed, but I’d say there’s slightly more on tap than the official 62mph.

The Yamaha NMAX 125 is light with a good steering lock and slim dimensions – perfect for wiggling to the front of a Portuguese traffic queue. The 13in wheels cope better with pot-holes and while the forks and twin rear shocks crashed over the city’s cobbles, Lisbon does have some of the craggiest tarmac in Europe.

ABS will be the biggest draw for most buyers and though the brakes aren’t linked, the anti-lock kicked in either front or rear on dry tarmac if they were grabbed too hard. I’d be glad of this at any time, let alone a wet and greasy A40 in December. Interestingly, Yamaha NMAX isn’t the only 125 scooter with standard ABS, but it is the only one at this price.

Everyday conveniences include enough under-seat room for a full-face lid, a small cubbyhole that’ll take a bottle of water and a shielded ignition lock that might resist inquisitive screwdrivers. The dash is all-digital and packed with information, including average/instantaneous mpg and an economy gauge. Fuel efficiency fetishists (of which I’m one), step this way.

And Here's Our Conversations with Shun Miyazawa, Product Manager, Yamaha :

Why Variable Valve Timing (VVA) ?

It gives the best of both worlds – good torque at low revs and good power at high revs. This technology works well with small cylinders, but we will be using it on bigger engines as well – a 150 and eventually a 250. It could also be used with multi-cylinder engines like that of the TMAX.

Isn’t ABS Expensive for a 125cc Scooter ?

Not really. We also wanted to be ready for compulsory ABS on 126cc and above bikes, which is coming next year in Europe. The high production volumes of the NMAX will bring economies of scale and make ABS cheaper for our other bikes.

Why no Idle-Stop System, Like the Honda PCX ?

Honda has patented this. Also, we wanted to have a different alternative, which is partly why we have VVA and ABS. We can have good fuel-efficiency without idle-stop.

The Return of Iconic Stars : World GP Legends Race !!

Some of racing’s most iconic stars have returned for the first of what could be a stunning new series... The World GP Legends Race !

History lived again at Spain’s Jerez GP track, with the fire-breathing 500cc V-Fours of the two-stroke GP era ridden by the skilful stars who raced them back then, contesting a trio of races that were very definitely the real deal, not just parades.

1987 500cc world champion Wayne Gardner grabbed the first win of the weekend aboard a 1989 ex-Randy Mamola Cagiva V589, just pipping Didier de Radiguès on a Suzuki XR89 RGV500 and Kevin Schwantz on the very same XR84 Suzuki that he defended his world title on in 1994. It was a close battle between the legends, with pole-sitter Christian Sarron dicing with Freddie Spencer for fourth place, both mounted on factory YZR500 Yamahas, after it proved impossible to source a track worthy Honda for the American two-time 500cc world champion to race.

In the first of Sunday’s two races it was Fast Freddie’s turn to take the flag ahead of Schwantz and de Radiguès – his first race victory of any kind since his AMA Superbike win at Laguna Seca in 1999. In the final contest, Schwantz grabbed the early lead, but was caught and passed by Spencer. Undeterred, the pair swapped positions several times before Kevin eventually made the move stick, to the delight of the sizeable crowd of Spanish race fans enjoying the return of the two-strokes, and the men who made them famous.

The 500cc GP spectaculars were the highlight of a packed weekend in southern Spain, with support races for 250/350cc and 125cc two-strokes, the latter won by four-time world champion Jorge ‘Aspar’ Martinez, taking time off from his day job as MotoGP team owner. Autograph sessions, stunt shows, trial displays and two live entertainment shows each evening in the paddock added to the on-track action.

British-based promoter, Nick Wigley, plans to stage four or five such events annually around the world in coming years. "The passion from the fans here at Jerez is like nothing I’ve ever seen," he said... "And the potential for this to become something on a global scale is really, really exciting. We hope everyone has seen just how special this can be, and we are already in discussions to take the event to more venues around the world."

Freddie Spencer said: "For us it’s brilliant to be back on the 500s again. I’ve been riding a bike I was actually racing against back in the Eighties! It’s a great connection between us guys up here, the collectors who have given us the opportunity to race these bikes again, and the fans who have come along to see us. I’m truly looking forward to where this is going in the future, and being a part of it."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)